How can we get water in the right place at the right time to help migrating birds?

Flocks of Dunlin use this flooded rice field as a place to rest during their long seasonal migrations. Farmers in the Great Central Valley of California are being paid to create temporary wetland habitat like this, at times that our models predict birds will need it most. Photo: © Drew Kelly

BirdReturns pairs birding and farmland management with innovations in big data, crowd-sourcing and online auctioneering.

Geese, ducks, cranes, and shorebirds need re-fueling stations along their seasonal migration routes. They stop to rest and forage ahead of the next leg of their journey. When wetlands disappear – as 90 percent of them have in the U.S. – critical links in a hemispheric chain of habitat “stepping stones” weaken. And as a consequence, one of the greatest biological phenomena on Earth – the bird migration along the Pacific Flyway – becomes increasingly imperiled.

A Conservancy scientist monitors shorebirds using a temporary wetland created by the BirdReturns Program, using a mobile app (developed by our conservation technology team) aimed at streamlining field data collection and analysis. Photo: © Drew Kelly

Over millennia, the Great Central Valley of California served as a linchpin of the Flyway, providing millions of acres of wetland habitat for migrating and overwintering birds. Over the last century, most of those wetlands were drained and replaced with intensive agriculture. Today, a small fraction of the once vast wetlands remain for the birds.

For many of the wetland dependent species of the Pacific Flyway, their long-term viability hinges on our ability to shore up the habitat they need, in a now very human-dominated landscape.

But how could we create more of the wetland habitat the birds need? Purchasing enough land is prohibitively expensive – in the billions of dollars. Yet, what if conservationists could instead “rent” the land the birds need, at the times and in the places the birds need it most?

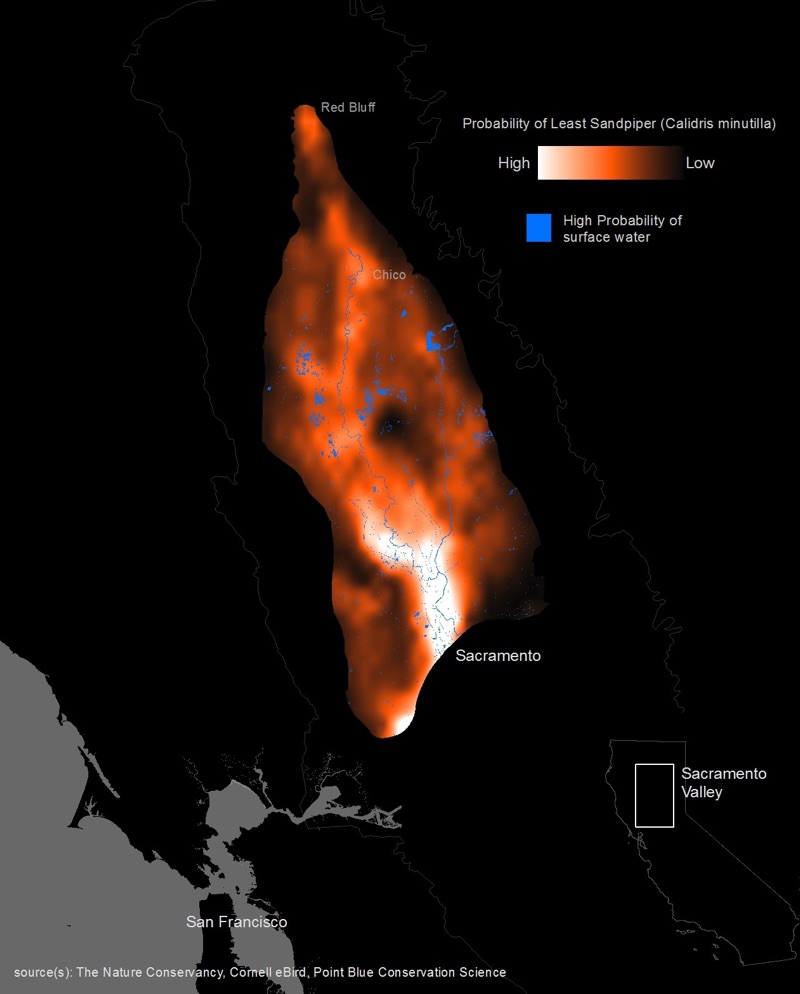

Figuring out whether renting could work first required us to figure out when the birds would need habitat. To answer this, our scientists partnered with researchers from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which had developed a mobile app – eBird – that birders use to record their observations. We worked with collaborators to analyze the millions of datapoints streaming in from these citizen scientists, to figure out the specific weeks birds in the Valley might most need habitat. Then, working with Point Blue Conservation Science, we mapped surface water availability using NASA satellite imagery to estimate the wetland habitat gap we needed to fill.

We also needed to figure out who would be willing to rent their farms for this purpose. We turned to rice farmers, as they typically flood their fields in winter to decompose stubble from the previous year’s harvest. That practice has long been recognized as bird friendly. Perhaps we could develop an incentive for those farmers to make it even friendlier – by encouraging farmers to delay draining their fields so as to give the birds the extra time they might need during that key period of the migration?

Our conservation scientists and economists mapped the annual migration cycle onto the agricultural cycle to figure out how we might be able to better synchronize them. We then launched an online “reverse auction” where farmers could compete for funds in exchange for keeping their land flooded for the period we determined to be most important. We could specify the weeks we sought flooded habitat, and even the depth of the resulting water (because some species may need just a few inches, others a foot or more). We evaluated bids based not just on the proposed price of renting the acreage, but also on the conservation value of the potential habitat a given farm might produce, based on proximity to wildlife refuges and so on.

Our conservation technology team developed mobile apps aimed at streamlining the various processes associated with running these auctions and monitoring compliance with the contracted terms – and, importantly, monitoring the response of the birds.

The response of birds to the temporary habitat provided by this program has been tremendous.

We are now exploring how to adapt BirdReturns to other types of farming across the state, with a goal is to create one million acres of habitat, doubling the Central Valley’s winter bird population.

Having a highly dynamic mechanism for creating temporary habitat that can complement the permanent protected areas along the Flyway is only going to grow more important as climates change and we’ll need to help species adapt to the more extreme patterns of drought and deluge expected for California.

This project is a case study of how emerging mobile technologies, citizen science, big data analytics, market-based tools, and muddy boots field science can come together to help solve a vexing conservation problem – with a dynamic and adaptable solution that actually can be applied at the hemispheric scale of the Flyway.

Model predictions for spring migration shorebird (least sandpipers in this case) abundances based on eBird data.

Gregory. H. Golet, Kristen. E. Dybala, Matthew. E. Reiter, Kristin. A. Sesser, Mark Reynolds, Rodd Kelsey

Shorebirds have declined precipitously in North America in the last 50 years, primarily due to the loss of wetlands. Incentive programs that pay farmers to create temporary wetland habitat on idled…O.J. Robinson, V. Ruiz-Gutierrez, M.D. Reynolds, G.H. Golet, M. Strimas-Mackey and D. Fink

Information on species’ habitat associations and distributions, across wide spatial and temporal scales, is fundamental for guiding conservation. Yet these data are often in short supply. In…Case study by: Khara Strum (Audubon California), Kristin Sesser (Point Blue Conservation Science), Greg Golet (TNC)

This case study communicates lessons learned by TNC and partners from years of research and monitoring of habitat enhancement projects in Sacramento Valley rice agriculture. It is a contribution to…Erin Conlisk, Gregory H. Golet, Mark D. Reynolds, Blake Barbaree, Kristin Sesser, Kristen Byrd, Sam Veloz, Matthew E. Reiter

Highly mobile species, such as migratory birds, respond to seasonal and yearly changes in resource availability by moving among habitats. Understanding how they select among habitats is important for…Matthew E. Reiter, Nathan K. Elliott, Dennis Jongsomjit, Gregory H. Golet, Mark D. Reynolds

In the Central Valley of California, with 90% of the historic wetlands gone, waterbirds depend upon managed wetlands and seasonally flooded agriculture to meet their habitat needs. The 2013-2015…Justine E. Hausheer, Mark D. Reynolds, Greg Golet

Gregory H. Golet, Candace Low, Simon Avery, Katie Andrews, Christopher J. McColl, Rheyna Laney, Mark D. Reynolds

Migratory birds face great challenges due to the climate change, conversion of historical stopover sites, and other factors. To help address these challenges, the Conservancy launched a dynamic…Mark D. Reynolds, Brian L. Sullivan, Eric Hallstein, Sandra Matsumoto, Steve Kelling, Matthew Merrifield, Daniel Fink, Alison Johnston, Wesley M. Hochachka, Nicholas E. Bruns, Matthew E. Reiter, Sam Veloz, Catherine Hickey, Nathan Elliott, Leslie Martin, John W. Fitzpatrick, Paul Spraycar, Gregory H. Golet, Christopher McColl, Scott A. Morrison

What if instead of buying habitat, conservationists could rent it when and where nature needs it most? The Conservancy is using predictive models of shorebird movements, data from the citizen science…Christopher J. McColl, Katie Andrews, Mark Reynolds, Gregory H. Golet

In response to the decline of wetland habitats for migrating and wintering water birds in California, the Conservancy developed a program called BirdReturns that creates “pop-up”…Eric Hallstein, Matt Miller

Brian L. Sullivan, Jocelyn L. Aycrigg, Jessie H. Barry , Rick E. Bonney, Nicholas Bruns, Caren B. Cooper, Theo Damoulas, André A. Dhondt , Tom Dietterich, Andrew Farnsworth, Daniel Fink, John W. Fitzpatrick, Thomas Fredericks, Jeff Gerbracht, Carla Gomes, Wesley M. Hochachka, Marshall J. Iliff, Carl Lagoze, Frank A. La Sorte, Matthew Merrifield, Will Morris, Tina B. Phillips, Mark Reynolds, Amanda D. Rodewald, Kenneth V. Rosenberg, Nancy M. Trautmann, Andrea Wiggins, David W. Winkler, Weng-Keen Wong, Christopher L. Wood, Jun Yu, Steve Kelling

This paper outlines how eBird has evolved from a basic citizen-science project into a collective enterprise, taking a novel approach to citizen science by developing cooperative partnerships…Stralberg, D., D. Cameron, M. Reynolds, C. Hickey, K. Klausmeyer, S. Busby, L. Stenzel, W. Shuford, G. Page

This analysis provides the first comprehensive overview of the specific habitats used by 42 different migratory waterbird species throughout California. The authors reveal important gaps in…